Kreator dokter perempuan bantu warga pedalaman Papua pahami kesehatan

Kesehatan adalah hal yang sangat penting bagi setiap individu. Namun, tidak semua orang memiliki akses yang sama terhadap informasi dan layanan kesehatan. Hal ini juga terjadi di daerah pedalaman Papua, dimana akses terhadap layanan kesehatan seringkali sulit dijangkau.

Untuk mengatasi permasalahan ini, sekelompok kreator dokter perempuan memutuskan untuk turun tangan membantu warga pedalaman Papua memahami pentingnya kesehatan dan bagaimana menjaga kesehatan mereka. Mereka menggunakan platform media sosial untuk menyebarkan informasi-informasi penting seputar kesehatan kepada masyarakat Papua yang tinggal di pedalaman.

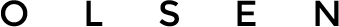

Dengan menggunakan bahasa yang mudah dipahami dan gambar-gambar yang menarik, kreator dokter perempuan ini berhasil menarik perhatian masyarakat Papua untuk peduli terhadap kesehatan mereka. Mereka memberikan informasi tentang pentingnya mencuci tangan, menjaga kebersihan lingkungan, serta mengenali gejala-gejala penyakit tertentu.

Tidak hanya itu, kreator dokter perempuan ini juga memberikan tips dan trik seputar gaya hidup sehat, seperti pola makan yang baik dan pentingnya berolahraga secara teratur. Mereka juga memberikan informasi tentang layanan kesehatan yang tersedia di daerah mereka, sehingga masyarakat Papua dapat dengan mudah mengakses layanan kesehatan yang mereka butuhkan.

Dengan adanya upaya dari kreator dokter perempuan ini, diharapkan masyarakat Papua di pedalaman dapat lebih memahami pentingnya kesehatan dan melakukan upaya-upaya preventif untuk mencegah penyakit. Selain itu, diharapkan pula bahwa akses terhadap layanan kesehatan di daerah pedalaman Papua dapat semakin meningkat, sehingga setiap individu dapat mendapatkan layanan kesehatan yang layak dan berkualitas.